Emerging Trends in Mammography

15 January 2019

By Inga Louisa Stevens, Contributing Writer

Breast cancer is the most common form of cancer among women impacting 2.1 million women worldwide. According to the World Health Organisation, in 2018, it is estimated that 627,000 women died from breast cancer — that is approximately 15 per cent of all cancer deaths among women. X-ray mammography has always been the ‘gold standard’ for routine screenings for breast cancer with the main aim being to help in the reduction of mortalities from breast cancer by bringing about an early detection of the disease, before the women feel the symptoms, and to detect cancer at a stage when it is most treatable.

Indeed, with this goal in mind, mammography has played a leading role. The Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium in North America carried out a study over six years, which included 401,548 examinations on 265,360 women. The study concluded that cancer detection, due to mammography, rose to 34.7 per 100 examinations.

As a stark increase from a previous such study conducted in 2005, which showed the cancer detection rate to be 25.3 per 100 examinations, these performance measures can serve as national benchmarks that may help to transform the marked variation in radiologists’ diagnostic performance into targeted quality improvement efforts.

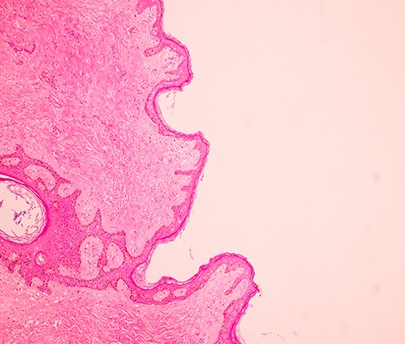

However, according to Dr. Lavina Verma, who is a specialist radiologist at Aster Clinic Bur Dubai, UAE, there are some shortcomings faced when mammography is used as the only radiological tool in order to assess a patient’s risk for breast cancer. “One of the primary reasons for the shortcomings is the presence of dense breast tissues (parenchymal tissue) in the breasts of some patients, which has resulted in false negative results (15 to 20 per cent) of mammograms for those patients that have dense breasts,” she explains.

As a result, healthcare professionals around the world agree that mammography can longer be used as a ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach and that there are ongoing efforts to develop and clinically translate alternative modalities that could provide for new contrast mechanisms and may potentially improve lesion detection and diagnosis. “The challenge is to use new technologies to increase cancer detection rates without also increasing recalls and false-positives,” notes Dr. Verma.

Some of the new and emerging technologies include:

- Digital Breast Tomosynthesis (DBT)

- Dedicated Breast Computed Tomograph

- Elastography

- Molecular Breast Imaging (MBI)

- Positron Emission Mammography (PEM)“A newer breast imaging modality Digital Breast Tomosynthesis (DBT) and more recently, Dedicated Breast Computed Tomography have been developed to alleviate the tissue superposition problem,” says Dr. Verma. “Increasingly, DBT is being used as an adjunct screening tool for the detection of breast cancer.”

DBT or 3D-mammography, is a mammography technique in which multiple mammographic images are acquired of compressed breast from multiple angles by using low dose x-rays and are then reconstructed into overlapping thin slices that can be displayed either individually or in a cine loop. The radiation dose received when DBT is combined with conventional 2D mammography is nearly double that of digital mammography alone, but within the established and acceptable safe dose.

Dr. Verma highlights a multi-centre clinical trial conducted by Hologic that has found that DBT takes only seconds longer than conventional 2D digital mammography, and can assist in increased cancer detection (by 27 per cent), increased invasive cancer detection (by 4 per cent) and decreased call-back rates (20-40 per cent), localising structures in the breast and improved lesion and margin visibility. Also, clinical data shows that 3D mammography was helpful for all breast densities.

“Multiple studies have demonstrated that with DBT, breast cancer detection rates are improved by 33–53 per cent (sensitivity) and that false-positive recall rates are simultaneously reduced by 30–40 per cent (specificity). However, all of these modalities rely upon x-ray attenuation contrast to provide anatomical images, and there are ongoing efforts to develop and clinically translate alternative modalities,” she explains.

“Ultrasound and Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) are two supplementary breast imaging modalities that retain their sensitivity in women with dense breasts, and when used in addition to mammography, can demonstrate an increased cancer detection rate compared to mammography alone,” adds Dr. Verma. “Elastography is another test that can be done as part of an ultrasound exam and is useful in revealing if the area is more likely to be cancerous or a benign (non-cancerous) tumour.”

According to Dr. Verma, the new emerging modalities like Molecular Breast Imaging (MBI) and Positron Emission Mammography (PEM) could provide for new contrast mechanisms and may potentially improve lesion detection and diagnosis.

MBI utilises a tracer and a custom camera in order to detect breast cancer. Unlike, mammograms, that take an x-ray image of the breast, MBI creates an image that shows a difference in the activity of the tissues. Those tissues that contain cancer cells can be identified because they appear to be brighter than their less active counterparts. PEM, on the other hand, works very similar to mammography, with the only difference being the injection of a positron and the use of a dedicated camera.

“The advantage of PEM over regular mammography is that it provides a far more specific image,” Dr. Verma says. “However, the drawback is that it cannot be used for regular breast cancer screenings, since the patient is exposed to slightly higher radiation doses as compared to other screening modalities.

”When asked about the basic rules for screening standards in the UAE, Dr. Varma outlines how breast cancer screening must be provided in accordance with the breast screening and diagnosis care pathway as provided by the The National Cancer Screening Committee. She also describes how, in addition, the following activities should be included:

- History and risk assessment

- Clinical breast exam (physical exam)¢ Screening mammogram — Screening mammography must involve two x-ray images for each breast; craniocaudal (CC) and mediolateral oblique (MLO).

- All women must be informed about the results of screening within three weeks (15 working days) of the date of screening mammogram.

- Women with abnormal mammogram, who require further assessment and diagnosis, must be recalled/referred to Diagnostic Breast Assessment unit within five working days of screening mammogram date.

- Assessment and diagnostic work up of screen-detected abnormality is best achieved using the triple assessment: 1. Imaging; usually diagnostic mammography and ultrasound; 2. Clinical examination; and 3. Image-guided needle biopsy for histological examination, if indicated.

- Cytology alone must not be used to obtain a non-operative diagnosis of breast cancer.

- Clinical examination is mandatory for every woman with a confirmed mammographic or ultrasound abnormality that needs needle biopsy and for all women recalled because of clinical signs or symptoms

According to the Abu Dhabi Department of Health (HAAD) screening guidelines, women should typically start having regular mammograms from the age of 40 onwards. And the screenings should be scheduled twice a year. However, for those women who have a family history or genetic predisposition to breast cancer, the screening age can be even earlier, at 30. Screening MRI and Ultrasound of the breast is recommended as adjunct to screening mammogram for women with dense breast/s or increased risk.

“In future, as assessment of risk and breast tissue density becomes a reality, more personalised screening will likely be added to that screening mammography regiment,” Dr. Varma concludes.

Want to exhibit at the 2021 edition of the show?

Register your interest to visit Arab Health 2021