Supply Chain Management: Top 5 Improvement Themes

By Inga Stevens, Contributing Writer

With the demand for healthcare across the world increasing, we are all seemingly locked in a battle to deliver higher quality, affordable care against a backdrop of escalating costs. And with around 30% of a hospital’s operational budgets spent on supply chain activities, what can be done to improve the way we currently manage supply chains in the Middle East?

The Middle East has a dynamic and innovative healthcare sector which has grown rapidly over the past few decades to rival any other in the developing or developed world. Indeed, with many regional governments in the middle of overhauling their public health systems, there are considerable opportunities for the private sector to fill the capacity and quality gaps.

“This growth has made the region attractive to the world’s largest pharmaceutical and medical equipment suppliers,” says Matthew Jones, Director in Health Industries Consulting for PwC Middle East. “However, despite this headway, many challenges remain in terms of healthcare supply chain management in the region.”

Based on PwC’s conversations with healthcare suppliers across the region, the picture is one of customer inefficiencies, a sense of not being treated as equal partners, inadequate training of hospital staff and consistently being paid late, amongst other complaints.

“Other challenges in the supply chain include the absence of good quality spend and inventory data, which significantly hinders a hospital’s ability to analyse their consumption and forecast accurately, which often leads to overstocking, obsolescence and waste,” explains Jones.

Capture, Control, Analyse, Enhance and Share

The team at PwC’s Health Industry practice believes hospitals can no longer afford to make purchasing and supply chain decisions on the basis of unit costs alone. Data-driven decision-making is essential to bring better value to all aspects of supply: for example, to realise efficient, precise inventory control and to manage supply chain operating costs.

“Off the back of these conversations and our own research, we have identified the ‘Top 5 Improvement Themes” that will most positively impact the health supply chain in the region, and allow hospitals to transform their practices to deliver benefits in both the cost and quality of care,” says Jones. “The central themes of ‘Capture, Control, Analyse, Enhance and Share’ can be effectively utilised to improve the inefficiencies in the way supply chain activities are currently managed.”

- Point-of-Use Data Capture

Hospitals currently have difficulties tracking stock consumption. Most buying decisions are made after manual checks on stock locations rather than from demand-driven forecasts or schedules. The supplies and contracting teams also have a limited understanding of clinical product preference or how well different products contribute to the best utilisation of clinical resources.

“Many hospitals do not have the right systems, tools or methods in place, leading to difficulties in evaluating quality of care vs. cost of a product or clinical activity,” says Jones. “However, low cost technologies such as bar code readers are now available to enable hospitals to unlock the value in supply chains.”

Capturing data at point of use means hospitals can:

- know the costs and productivity at the point-of-care

- make live demand forecasting and purchasing decisions

- improve the cost management and quality of care

“Capturing data closer to the point of delivery and investing in point-of-use technologies is key to unlocking further supply chain and procurement improvements,” adds Jones.

Figure 1: Point-of-Use Data Capture using a Bar Code Reader – Source: PwC

- Control Tower Management

Few hospitals have end-to-end supply chain visibility. They do not have a central overview of inventory levels, purchase orders or the productivity of their workforce. Decisions are made in silos and only in the interest of a department, not the hospital as a whole. As a result, hospitals are unable to track performance, forward plan or make decisions based on demand and supply. Opportunities to share resources across specialties, sites or even hospitals are lost and the ability to make cost savings, severely diminished.

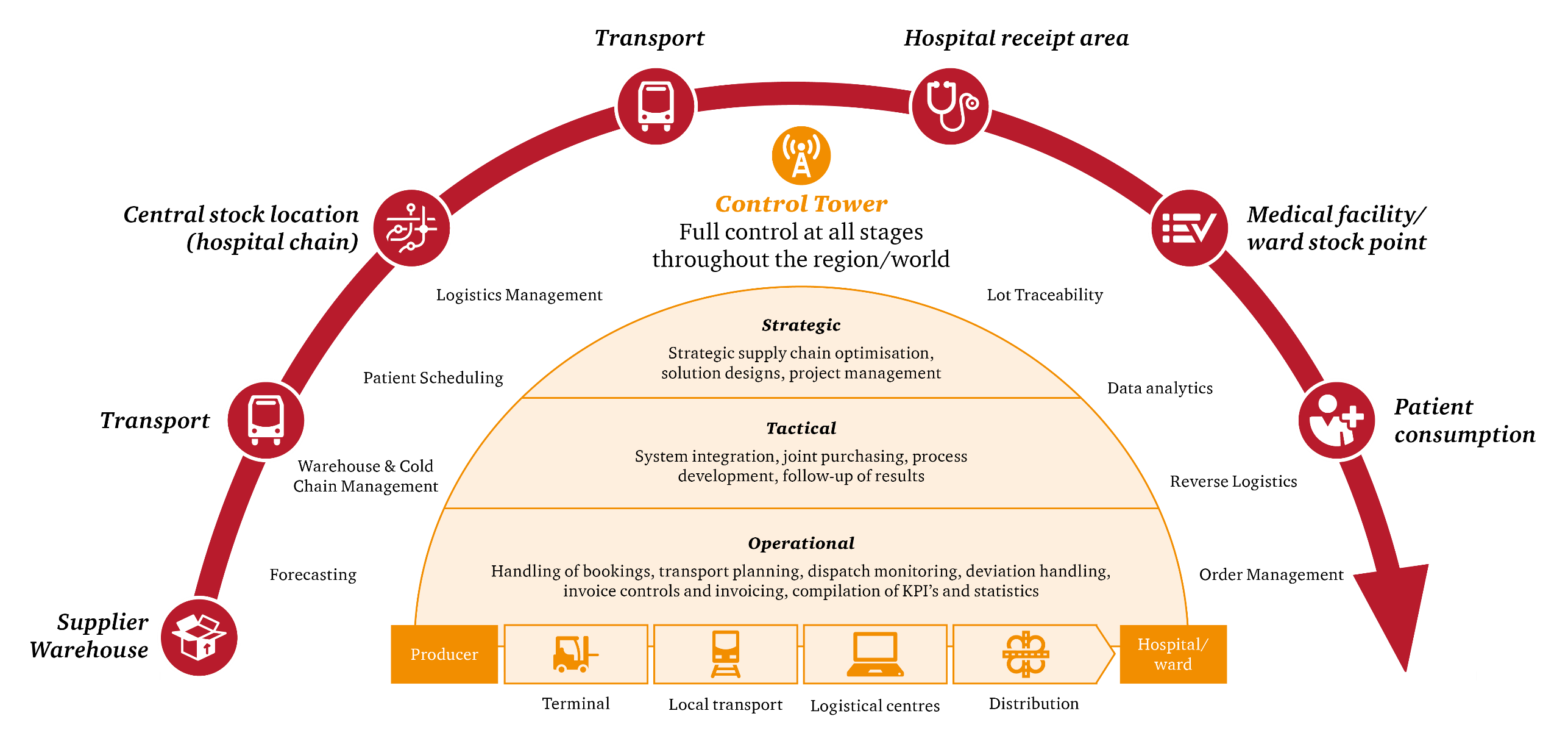

The concept of having a centralised, end-to-end view of supply chain operations has become an increasingly popular concept with the pharmaceutical and retail industries in recent years. This if often referred to as a Control Tower (see Figure 2), which acts as a central point of coordination with multiple capabilities including logistics, contract management, data analytics and forecasting, allowing for complete visibility across these functions. This concept can be easily replicated by hospitals.

According to Jones, “Control Towers become more effective as services are scaled or shared between organisations. These benefits can be used to improve collaboration across hospital systems and their supply chains.”

Figure 2: Visualization of a Control Tower – Source: PwC

- Analyse Clinical Variation

Understanding clinical variation in medical practice is an important step for measuring efficiency and effectiveness in care delivery. Clinical variation in hospitals across the specialty areas and healthcare facilities is a significant cost driver.

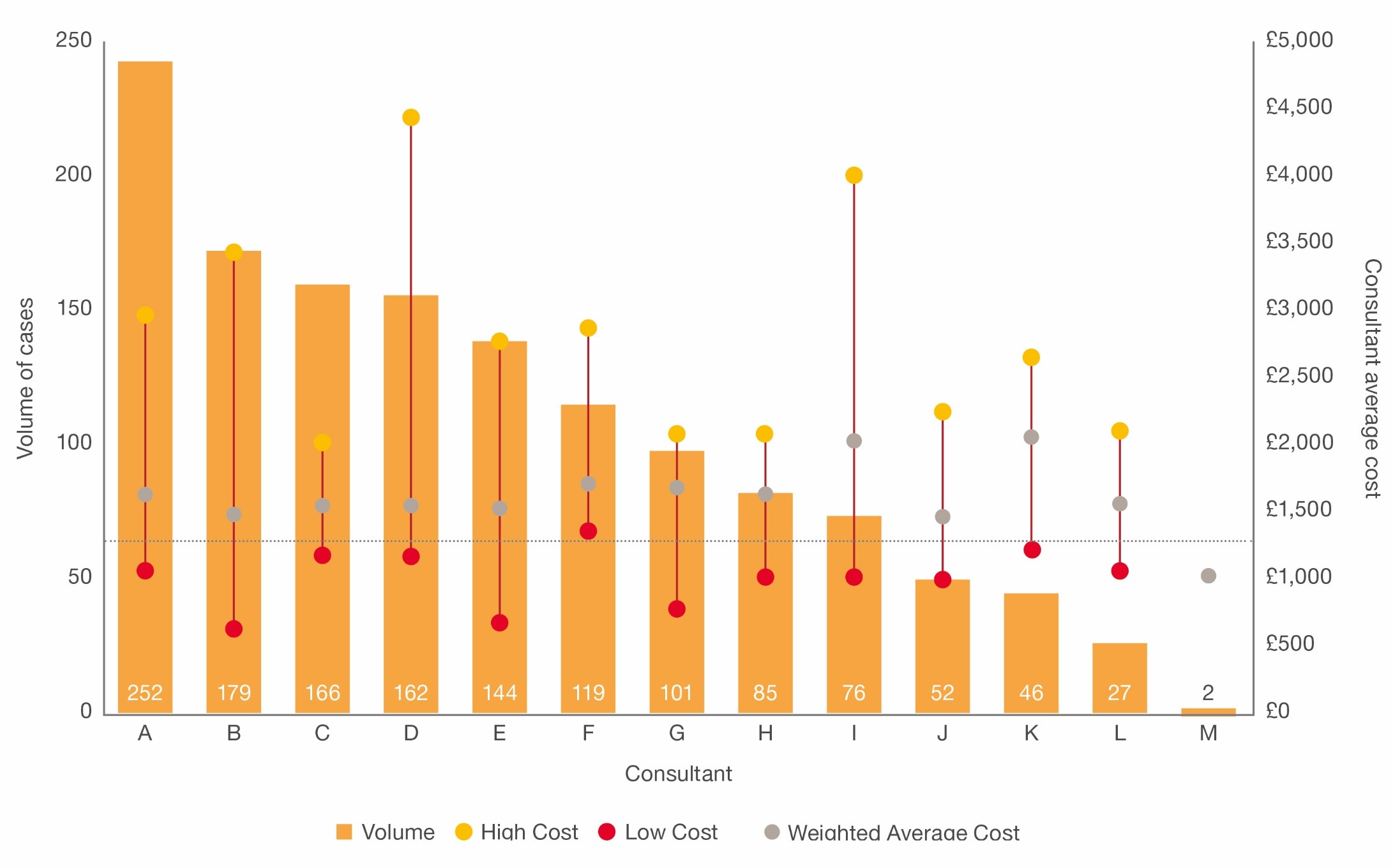

In PwC’s analysis of hip systems consumed in a typical UK hospital Operating Rooms, they observed significant variance to the average cost per procedure per clinician which was slightly above £1,500 ($1,900), as illustrated in the graph below. This indicated that clinical choice of supplier and type of fixation is a primary driver for variance in cost. With this analysis, they helped the hospital identify a realistic opportunity to reduce the average cost per procedure by 40%.

Figure 3: Hip systems cost variance by consultant in a UK hospital - Source PwC analysis

“Hospitals in the Middle East are currently trying to reduce costs through standardisation of usage and price negotiations,” says Jones. “However, these activities are not supported by evidence as data is not routinely collected. In addition, limited clinical involvement in these decisions makes sustainable change more unlikely.”

The following four actions can contribute to reducing clinical variation:

- capture spend and product preference

- use data to evaluate and accelerate innovation

- establish Clinical Reference Groups

- restructure kits based on standard procedural needs

Jones believes that as well as making financial savings, clinical teams will be able to share information on devices and make informed decisions on ‘cost versus value’ to minimise waste whilst improving overall outcomes.

- Enhance Supplier Relationships

Historically, Jones says, relationships between suppliers and hospital procurement teams in the region have been transactional, based on short-term gains with few partnerships, and often a one-size-fits-all interpretations of procurement rules.

“The short-term transactional relationships have mainly focused on volume, price reduction or product availability as opposed to delivering value such as patient outcomes or continuous improvement through long-lasting partnerships,” Jones explains. He says that in some instances, suppliers are willing to share the risk of inventory via consignment stock, but hospitals in this region rarely have the level of trust in the supplier relationship to enable these deals to materialise.

Hospitals should therefore:

- develop supplier relationship management frameworks and capabilities

- share demand signals with suppliers

- pursue an outcomes-based approach

“Focusing on strategic relationships will enable hospitals to ultimately find the right supplier, pay the right price and create partnerships for the right patient outcomes,” he adds.

- Share and Manage Inventory Strategically

Hospitals need to have more strategic control over managing their inventory in order to release cash and control spending. The UK Government Lord Carter report on operational productivity in acute hospitals suggests that in medicine cabinets stockholding varies from 11 to 36 days, with no obvious logic for this variance. “With strategic inventory management, it doesn’t have to be like this,” says Jones.

Most commonly, hospital supply chains have a decentralised footprint of inventory locations within their institutions, with medical supplies ordered and monitored close to the delivery of care. This leads to significant excess in medical supply often with similar products held in multiple sites within a hospital or across hospital chains. PwC’s analysis has shown that hospital staff tends to justify holding excess inventory because they do not have visibility of the overall stock requirements of the hospital.

According to Jones, centralising inventory management and optimising the usage of procedure kits can overcome this overstocking. Some ways to deliver this are:

- Introduce better visual management of performance

- Pool inventory risk across the hospital

- Create readily available procedure carts/kits

- Introduce and train staff in inventory and order management rules

- Have central supply chain teams

“Our findings tell us that strategic inventory management can reduce stocks by 25-40% whilst eliminating waste and reducing the administrative burden on clinical teams from supply chain activities,” he adds.

A Strategic Enabler

Hospitals in the region have a far greater potential to save money and deliver better quality outcomes by placing supply chain management at the forefront, and as a strategic enabler. With the increasing availability of low cost technologies such as bar code readers, or the adoption of centralised overview mechanisms that allow for complete visibility of a hospital’s supply chain functions, hospitals are in a position to unlock the value in supply chains.

“Focusing on these Top 5 Improvement Themes of “Capture, Control, Analyze, Enhance and Share” can help hospitals transform their practices to deliver a host of benefits in the cost and quality of care,” says Jones.