Healthcare & general services in the GCC

Amidst an ageing and expanding population, and the increasing prevalence of lifestyle diseases, the healthcare sector is fast emerging as a priority for Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries as they work to diversify their economies away from a reliance on oil production.

The report will focus on infrastructure investments and how customer centricity will play an increasingly important role in the evolution of the region’s healthcare industry with patient experience becoming a priority for both public and private players. Major developments in technology, an influx of medical tourists, as well as changing patient needs are also emerging as major drivers for the bourgeoning GCC healthcare landscape.

View the report to find out more

Introduction

Amidst an ageing and expanding population, and the increasing prevalence of lifestyle diseases, the healthcare sector is fast emerging as a priority for Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries as they work to diversify their economies

away from a reliance on oil production.

With governments continuing to pass reforms in their healthcare systems and introduce regulatory changes to improve the efficiency and quality of services, the current healthcare expenditure in the GCC is projected to reach US$ 104.6 billion in 2022 from an estimated US$ 76.1 billion in 2017, implying a CAGR of 6.6%, according to a 2018 GCC Healthcare Industry Report by Alpen Capital.

Historically, government authorities in the GCC have functioned as both investors and operators of healthcare facilities, however, as their roles are now being adapted to that of policymakers and regulators only, there is a marked increase in participation by private players.

Various National Transformation Plans (NTPs) and policy programmes such as the UAE Vision 2021 and the Saudi Vision 2030 are outlining long-term government strategies to expand the role of the private healthcare sector and create additional capacity for their growing markets. In turn, increasing investments by these sectors is expected to create a strong demand for pharmaceutical products, medical equipment and supplies, hospital services andhealthcare professionals, easing the demand on the public sector.

In addition to infrastructure investments, customer centricity will play an increasingly important role in the evolution of the region’s healthcare industry with patient experience becoming a priority for both public and private players.

Major developments in technology, an influx of medical tourists, as well as changing patient needs are also emerging as major drivers for the bourgeoning GCC healthcare landscape.

GCC healthcare predictions for 2022:

- Average health inflation to remain at around 4.0%

- Healthcare expenditure projected to reach US$ 104.6 billion

- Outpatient market size to grow to US$ 32.0 billion

- Inpatient market projected to contribute 43.4% of healthcare expenditure

- The region is expected to require 12,358 new hospital beds

National agenda for a world-class healthcare system

Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030, a blueprint for the transformation of the Saudi economy away from its overreliance on oil and the public sector, was unveiled in April 2016.

Shortly after, specific targets of the Vision 2030 agenda were outlined in the release of the Saudi National Transformation Plan (NTP).

According to research from Knight Frank, healthcare is one of the main focus areas of the Vision 2030 and the NTP. The Kingdom’s healthcare plan under the NTP has placed the sector on a fast trajectory to privatisation and growth over the coming years.

Targets set out by the NTP for the Ministry of Health (MoH) for the year 2020 include:

- Increasing private healthcare expenditure from 25% to 35% of total healthcare expenditure

- Increasing the number of licensed medical facilities from 40 to 100

- Increasing the number of internationally accredited hospitals

- Doubling the number of primary healthcare visits per capita from two to four

- Decreasing the percentage of smoking and obesity incidence by 2% and 1% from baseline respectively

- Doubling the percentage of patients who receive healthcare after critical care and long-term hospitalisation within four weeks from 25% to 50%

- Focusing on improving the quality of preventive and therapeutic healthcare services

- Increasing focus on digital healthcare innovations

United Arab Emirates

In the UAE, providing world-class healthcare is one of the six pillars of the National Agenda in line with the UAE Vision 2021, which was unveiled by H.H. Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum, Vice-President and Prime Minister of the UAE and Ruler of Dubai, in 2010.

As part of the National Agenda, the UAE government will work in collaboration with all health authorities in the country to have all public and private hospitals accredited according to clear national and international quality standards of medical services and staff.

Also, the National Agenda emphasises the importance of preventive medicine and seeks to reduce cancer and lifestyle-related diseases, reduce the prevalence of smoking and increase the healthcare system’s readiness to deal with epidemics and health risks.

Key Performance

Indicators (KPIs) to measure its performance against its healthcare targets for

2021 include:

- Number of deaths from cardiovascular diseases per 100,000 population

- Prevalence of diabetes n Prevalence of obesity amongst children

- Average healthy life expectancy

- Prevalence of smoking any tobacco product

- Number of deaths from cancer per 100,000 population

- Percentage of accredited health facilities

- Healthcare Quality Index

- Number of physicians per 1,000 population

- Number of nurses per 1,000 population

Bahrain

Under Bahrain’s Economic Vision for 2030, which was launched in October 2008, all Bahraini nationals and residents are to have access to quality healthcare. The aim is to have Bahrain become a leading centre for modern medicine, offering highquality and financially sustainable healthcare in the region and for patients to have the choice of public and private providers that meet international standards for healthcare provision.

The Vision 2030 outlines a plan for the health system in Bahrain to cater to the healthcare needs of its rapidly growing and ageing population and will address the key risk factors.

The government will play a vital role in improving the health system along the following levers:

- Promoting and encouraging a healthy lifestyle

- Providing quick, easy and equitable access to high-quality healthcare

- Ensuring the regulation of the healthcare system by an independent health regulator

- Developing, attracting and retaining healthcare talent and fostering a

highperformance ethic among all healthcare employees

Oman

The Centre of Studies and Research in Oman’s MoH released a long-term strategic plan in 2014 - the ‘Health Vision 2050 for Health Research’ – with the aim of making Oman the regional leader and a research hub of world standards in health research.

The mission is to promote, facilitate, and conduct high-quality health research addressing national health priorities to improve healthcare services and enhance the efficiency and effectiveness of the health system, reduce health inequity, and contribute to socioeconomic development.

According to Oxford Business Group, in the short term, Oman’s ninth five-year plan, which runs from 2016 to 2020, focuses on the building of integrated medical cities for the healthcare sector, investing further in human resource development, restructuring medical education and significantly boosting health care spending.

Kuwait

The Kuwaiti government’s development plan, ‘Vision 2035’, aims to turn Kuwait into a regional financial, cultural and institutional leader and to reduce dependency on oil.

The reform of the healthcare sector is integral to this plan, and the government has begun implementing a number of reforms aimed at improving service quality in the public healthcare system and developing national capabilities at a reasonable cost.

Kuwait’s healthcare targets for 2035 include:

- Improving the quality of healthcare services

- The mitigation of chronic Non-Communicable Diseases (NCDs)

- The increase of bed capacity in hospitals

The regulatory environment

As healthcare spending in GCC countries increases and new healthcare facilities, services and treatment options enter the market, the healthcare regulatory structure in the GCC must adapt to support these developments.

In Saudi Arabia, the MoH is the regulator for most of the healthcare sector in Saudi Arabia. Separately, the Ministry of Defence, including the National Guard, maintains its own standards. According to an article published in the Law Reviews, Saudi Arabia is currently liberalising its regulations to encourage more foreign participation in the healthcare sector in Saudi Arabia with the opportunity for investment to further accelerate in the coming years.

Meanwhile, in the UAE, the Ministry of Health and Prevention (MoHP) is the federal health authority. After the establishment of individual emirate-based healthcare authorities by Abu Dhabi and Dubai, the focus of the MoHP was shifted to the Northern Emirates (Sharjah, Ajman, Umm Al Quwain, Ras Al Khaimah and Fujairah). The Department of Health-Abu Dhabi is responsible for licensing, quality control and regulating all the healthcare facilities and health professionals in the emirate of Abu Dhabi. The Health Regulation Sector (HRS), under the Dubai Health Authority, has been tasked with developing regulations, standards and guidelines pertaining to healthcare professionals and health facilities, as well as the licensing of health facilities and healthcare professionals in Dubai.

In Bahrain, the MoH oversees Bahrain’s network of public hospitals, clinics and specialised healthcare centres. The National Health Regulatory Authority (NHRA), made into a separate body in 2009, is responsible for inspecting public and private healthcare facilities, licensing medicines and medical personnel, as well as addressing complaints. In 2012, Bahrain established the Supreme Council for Health, which is charged with strategic planning with the aim of making each public sector hospital in Bahrain autonomous.

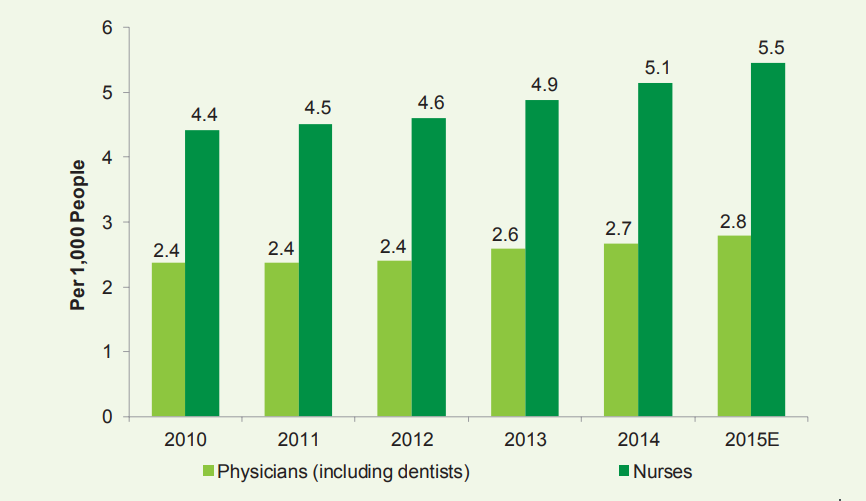

Exhibit 13: Physicians and Nurses Density in the GCC

Source: Health Ministries of Bahrain, Oman, Qatar and Saudi Arabia, FCSA, CSB, MDPS, IMF, Alpen Capital

The MoH oversees the healthcare sector in Oman while the Central Quality Control Laboratory is responsible for ensuring the quality, safety and efficacy of pharmaceutical products in the country.

Kuwait’s MoH is the owner, operator, regulator, and financer of the vast majority of healthcare services rendered, pharmaceuticals purchased, and medical equipment acquired in the country. According to a report by IMS Health, there continues to be a strong need to create an independent healthcare regulatory authority that will spearhead the policy development, licensing, quality assurance and the overseas healthcare functions in Kuwait.

The shortage of healthcare professionals

According to Alpen Capital, a high dependence on expatriates and inherent scarcity of skilled and experienced physicians and nurses has been one of the major factors hindering the growth of the healthcare sector in the GCC. On average, the GCC had 5.5 nurses and 2.8 physicians and dentists per 1,000 persons in 2015. While the physicians (including dentists) to population ratio is close to that in the other developed countries, the region faces a dearth of nursing staff.

With new hospital developments underway, the competition to hire experienced and skilled physicians, nurses and allied workforce is set to intensify. To meet the growing need of qualified healthcare professionals, the regional governments are investing in education and expansion of medical colleges to strengthen the domestic workforce.

A focus on positive patient experience

As described by the US Department of Health & Human Resources, understanding patient experience is a crucial step in moving toward patient-centred care. Also, evaluating patient experience along with other components such as effectiveness and safety of care is essential to providing a complete picture of health care quality.

In the GCC, there are ongoing plans to move away from the traditional healthcare model and develop more customer-centric environments. For example, as part of its Dubai Health Strategy 2016-2021, the Dubai Health Authority included customercentricity as one of its six values, alongside efficiency, an engaged and motivated workforce, accountability and transparency, innovation, and excellence. Similarly, Saudi Arabia’s Ministry of Health is striving for “a safe, quality health system, based on patient-centric care, guided by standards, enabled by eHealth.”

According to a 2017 EY Report titled ‘What is the cure for a better patient experience in the GCC?’, 85% of GCC patients want a stronger patient experience from healthcare providers. Furthermore, 38% of those surveyed have trust in their local healthcare system, and most patients reported they would opt to get care for serious conditions outside the GCC region.

From regulatory bodies to providers, the report found that many healthcare organisations in the GCC region lack a mature patient experience management function despite 82% of healthcare professionals indicating that patient experience is a priority in their organisation. In the same survey, 51% of the healthcare professionals rate overall healthcare quality as inconsistent.

Potential solutions to manage patient experience in the GCC:

- Digitisation of electronic medical records

- Mobile applications

- Remote patient monitoring

- AI

- Telemedicine

- Automation of medical centres

- Citizen health

- Preventative health education

Becoming a medical tourism destination

According to Alpen Capital, medical tourism is an integral part of the economic diversification plans of the GCC countries and, subsequently, has been receiving stimulus from governments. With improving infrastructure and quality of services, the region will not only experience a rise in medical tourists but also may witness a drop in outbound medical tourism.

The UAE is one of the fastest growing medical tourism hubs globally. In 2018, Dubai welcomed 326,649 medical tourists - a 9.5% increase from 2015 - and aims to receive 500,000 tourists by 2020 by relaxing visa procedures and holding promotions generating revenues of US$ 707.7 million. Abu Dhabi is also establishing a medical tourism network to attract and serve patients from Russia, China and India.

Following in the footsteps of the UAE, other GCC countries are also working towards building a robust infrastructure and investing in state-of-the-art technologies to appeal to international medical tourists.

Bahrain is hoping to benefit from the rise in medical tourism, in particular when it comes to patients visiting from Saudi Arabia, according to Oxford Business Group. Significant projects include Dilmunia Health Island and the King Abdullah Medical City, with media reports suggesting that Bahrain is targeting Russian investors to develop healthcare facilities for medical tourists.

Medical tourism index ranking Arabic region (2017):

- 1st Dubai

- 2nd Abu Dhabi

- 7th Oman

- 9th Kuwait

- 10th Saudi Arabia

- 11th Bahrain

Meanwhile, in Oman, public healthcare is perceived as being of high quality for a middle-income country, which allows the Sultanate to compete in the medical tourism industry for incoming patients. Oman is currently constructing the International Medical City, which is poised to become the centrepiece of healthcare tourism benefiting local, regional and international healthcare patients alike.

The Government of Kuwait has ambitions to welcome 440,000 visitors a year by 2024 and is pressing ahead with multiple plans that will see billions of dollars invested in projects. Plans are also in place to establish a Supreme Commission for Tourism to initiate its tourism strategy, and Kuwait is also planning to promote medical tourism in its own country by developing world-class healthcare facilities. In Saudi Arabia, as most of the tourism involves religious pilgrimages with tourist visas difficult to obtain, this makes the medical tourism industry a complicated industry, according to the Medical Tourism Index. However, the government’s spending on medical technology and state-of-the-art facilities can someday represent real competition to other countries in the region.

Where the healthcare world comes to do business

Arab Health is an essential platform to conduct healthcare business in the MENA region – having attracted over 55,500 attendees from all over the globe to meet with 4,150 exhibiting companies in 2019. Our first-class exhibition, combined with high-quality accredited medical conferences, has continued to grow and bring investment and new technologies into the Middle Eastern healthcare community for 45 years.

The 2022 post show report is now available

Want to exhibit at the 2023 edition of the show?